Magic without consequences is like a fairy offering without milk: unlikely to get you killed, but kinda incomplete. The best books about magic are the kind that extract something from their characters on their way through the magical wringer, be it health or sanity or time. Think Thomas the Rhymer losing seven years beneath a fairy hill, or Quentin Coldwater coming out of a magical coma with white hair, a wooden shoulder, and a dead girlfriend.

Here are five more tales in which magic has a price.

Worlds of Ink and Shadow by Lena Coakley

Coakley’s novel takes on the strange, sad legacy of the Brontë siblings: their life in a parsonage at the edge of a lonely moor, their literary genius, their early deaths. Famously, the siblings created an imaginary realm called Glass Town, the setting for their juvenile writings. In Coakley’s hands, Glass Town becomes a fully populated otherworld in which the Brontës are both players and gods. But as their creations become sentient, and evidence grows of a snake in the garden, they discover the costs of playing at creator are heartrendingly high. The book’s wistful, inevitable ending marries invention with historical record, and it still hangs on my heart.

Coakley’s novel takes on the strange, sad legacy of the Brontë siblings: their life in a parsonage at the edge of a lonely moor, their literary genius, their early deaths. Famously, the siblings created an imaginary realm called Glass Town, the setting for their juvenile writings. In Coakley’s hands, Glass Town becomes a fully populated otherworld in which the Brontës are both players and gods. But as their creations become sentient, and evidence grows of a snake in the garden, they discover the costs of playing at creator are heartrendingly high. The book’s wistful, inevitable ending marries invention with historical record, and it still hangs on my heart.

Vassa in the Night by Sarah Porter

The peril of messing with magic in Porter’s Russian myth-inspired tale is a mortal one: not everyone gets away with their head. Vassa is an underloved sister in an overstretched family in a magical alt Brooklyn, where the manipulations of a barely disguised Baba Yaga have made the nights go elastic and endless, stretching far beyond the hours between dusk and dawn. Baba Yaga is reimagined as Babs, proprietor of 24-hour convenience store BY’s, which claims to cater to night owl customers but mainly frames them for shoplifting and beheads them. Vassa manages to escape decapitation, but is pressed into three nights’ service at BY’s, where she fights to hold onto her life and to discover the secrets behind the endless nights–while putting the person (so to speak) most dear to her on the line.

The peril of messing with magic in Porter’s Russian myth-inspired tale is a mortal one: not everyone gets away with their head. Vassa is an underloved sister in an overstretched family in a magical alt Brooklyn, where the manipulations of a barely disguised Baba Yaga have made the nights go elastic and endless, stretching far beyond the hours between dusk and dawn. Baba Yaga is reimagined as Babs, proprietor of 24-hour convenience store BY’s, which claims to cater to night owl customers but mainly frames them for shoplifting and beheads them. Vassa manages to escape decapitation, but is pressed into three nights’ service at BY’s, where she fights to hold onto her life and to discover the secrets behind the endless nights–while putting the person (so to speak) most dear to her on the line.

Akata Warrior by Nnedi Okorafor

In the follow-up to Okorafor’s middle-grade novel Akata Witch, Nigerian American teen Sunny has grown up into a YA-aged heroine, and into her status as a magical Leopard Person. The portal world she navigates, Leopard Knocks, is a lush and feral one, where books written in enchanted scripts can eat you alive, a brutal masquerade stalks her with single-minded focus, and nobody can protect her after she uses her magic to exact revenge on a loved one’s human-world tormentors. Where Harry Potter had detention in the unpredictable Forbidden Forest, Sunny must serve her time in the basement of the Leopard Knocks library. This sequence is the book’s scariest, marooning Sunny in a place perched beyond the reach of her adult mentors, where the line between life and death is thin and a patient evil awaits.

In the follow-up to Okorafor’s middle-grade novel Akata Witch, Nigerian American teen Sunny has grown up into a YA-aged heroine, and into her status as a magical Leopard Person. The portal world she navigates, Leopard Knocks, is a lush and feral one, where books written in enchanted scripts can eat you alive, a brutal masquerade stalks her with single-minded focus, and nobody can protect her after she uses her magic to exact revenge on a loved one’s human-world tormentors. Where Harry Potter had detention in the unpredictable Forbidden Forest, Sunny must serve her time in the basement of the Leopard Knocks library. This sequence is the book’s scariest, marooning Sunny in a place perched beyond the reach of her adult mentors, where the line between life and death is thin and a patient evil awaits.

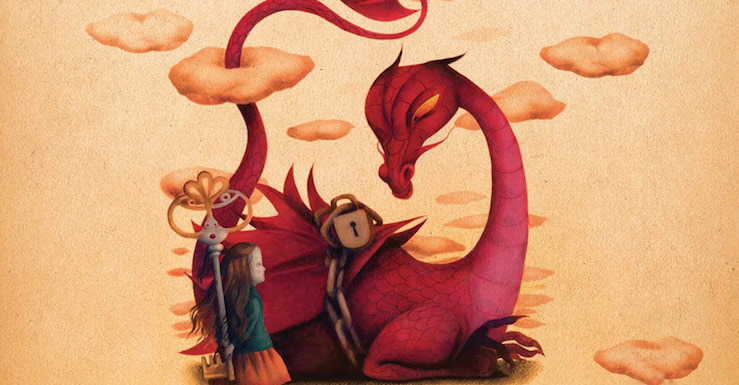

The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making by Catherynne M. Valente

There’s a scene in the first installment of Valente’s hallucinogenic Fairyland series in which fairyland interloper September makes a fateful deal. The Glashtyn, horse-headed aquatic fey, demand a tithe from the ferry passing over their waters: a young Pooka girl passenger. September valiantly intercedes, and the Glashtyn accept, as alternative payment, September’s shadow. Most portal-world visitors make it back home with all their pieces intact, so this moment strikes an eerie note of permanency. How can September go home now, shadowless? The loss is nearly swept out of mind by every dazzling thing that follows, but comes back to haunt September in book two, The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There: unmoored from September, her shadow leads a magic-draining, shadow-stealing revolution in Fairyland Below, as fearsome ruler the Hollow Queen.

There’s a scene in the first installment of Valente’s hallucinogenic Fairyland series in which fairyland interloper September makes a fateful deal. The Glashtyn, horse-headed aquatic fey, demand a tithe from the ferry passing over their waters: a young Pooka girl passenger. September valiantly intercedes, and the Glashtyn accept, as alternative payment, September’s shadow. Most portal-world visitors make it back home with all their pieces intact, so this moment strikes an eerie note of permanency. How can September go home now, shadowless? The loss is nearly swept out of mind by every dazzling thing that follows, but comes back to haunt September in book two, The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There: unmoored from September, her shadow leads a magic-draining, shadow-stealing revolution in Fairyland Below, as fearsome ruler the Hollow Queen.

Peter Pan by J.M. Barrie

There’s a line in Peter Pan that has rattled around my brain since I first read it as a kid. The Lost Boys access their underground home via the trunks of hollow trees, one for each boy—but if your tree doesn’t fit you just right, it isn’t the tree that’s adjusted: “If you are bumpy in awkward places or the only available tree is an odd shape, Peter does some things to you, and after that you fit.” No more is said about what kind of surgeries Pan performs on his army of children, but it’s just one of the glitteringly heartless moments strewn throughout J.M. Barrie’s kids’ classic. The herd of Lost Boys fluctuates in size as kids arrive from the mainland, are dispatched by pirates, or, most tragically of all, make the fateful decision to go back to London with the Darling children. The costs of letting go of magic are painfully high, too: by the time they realize they’ve made a terrible mistake in leaving the Neverland behind, it’s too late to return.

There’s a line in Peter Pan that has rattled around my brain since I first read it as a kid. The Lost Boys access their underground home via the trunks of hollow trees, one for each boy—but if your tree doesn’t fit you just right, it isn’t the tree that’s adjusted: “If you are bumpy in awkward places or the only available tree is an odd shape, Peter does some things to you, and after that you fit.” No more is said about what kind of surgeries Pan performs on his army of children, but it’s just one of the glitteringly heartless moments strewn throughout J.M. Barrie’s kids’ classic. The herd of Lost Boys fluctuates in size as kids arrive from the mainland, are dispatched by pirates, or, most tragically of all, make the fateful decision to go back to London with the Darling children. The costs of letting go of magic are painfully high, too: by the time they realize they’ve made a terrible mistake in leaving the Neverland behind, it’s too late to return.

Melissa Albert is the founding editor of the Barnes & Noble Teen Blog and the managing editor of BN.com. She has written for McSweeney’s, MTV, and more. She lives with her husband in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, where she reads, swims, and experiments in the kitchen. Her novel The Hazel Wood is available now from Flatiron Books. You can find her on Twitter @mimi_albert.

Melissa Albert is the founding editor of the Barnes & Noble Teen Blog and the managing editor of BN.com. She has written for McSweeney’s, MTV, and more. She lives with her husband in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, where she reads, swims, and experiments in the kitchen. Her novel The Hazel Wood is available now from Flatiron Books. You can find her on Twitter @mimi_albert.